|

|

Should a .410 be in your battery? - Page 3 |

|

|

Paper cases were generally used for .410 shells until 10

years ago. There were some interesting exceptions. About the time of World

War 1, the old U.S. Cartridge Co. made solid brass cases. Aluminium cases

were used for .410 shot and rifled slug shells loaded for survival guns

made during Word War II. It was always difficult to load a full ¾

oz. of shot in the 3” case. It became even more so when plastic

shotsleeve wads further reduced the already small volume. Today’s 3”

factory loaded shell shoots 11/16 oz. of shot at a muzzle velocity of 1135

f.p.s. The 2½” shell shoots ½ oz. shot load at 1200 f.p.s. |

|

|

|

Both plastic cases have a six-point folded crimp. They

are loaded with shot sizes No. 4, 6, 7½, 8 and 9. I believe it would be

just as well if the two largest sizes and the rifled slug were dropped.

Their availability encourages uses for which the .410 is not suited.

While velocity and energy per pellet are not materially different from

those of the larger bores, low pattern density limits the .410’s

effectiveness. This is best dealt with by using fine shot to increase

the total pellet count. No. 8 is probably the largest size suitable. For

most purposes No. 9 is better. Contrary to popular belief, .410 patterns are not

smaller in diameter then those of larger bores having the same choke. In

fact, they sometimes get larger because a higher percentage of the

pellets are deformed in their passage down the .410 bore. A few true experts use .410 guns creditably in the

field. More than wing-shooting skills are involved. Recognition of the

guns limitations and the ability to judge range are important as

pointing skill in avoiding unacceptable crippling losses. Those

thoroughly familiar with its limitations seldom recommend the .410 as a

beginners gun. A 20-ga. with light loads is much more satisfactory

because of the better chances of early success.

|

|

For those who value light carrying weight in the field

and are sensitive to recoil, the 28-ga. provides a highly recommendable

alternative. An acquaintance of long experience has fired thousands of

patterns from .410 bore to 28-ga guns. He now uses both for skeet but only

the 28-ga. in the field. His unforgettable succinct reason, “The 28-ga.

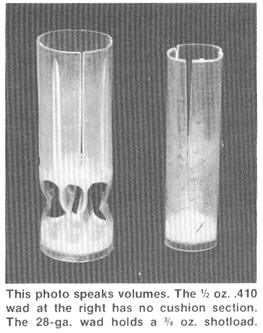

is a lot more like a gun.” Reloading .410 shells has its own peculiar problems and rewards. The outstanding reward is financial. Factory loaded .410 shells cost about the same as 12-ga. loads. There is no saving using the smaller bore if you shoot factory ammunition. Hand loaded shells are another thing. The cost of shot is more than that of the other components combined, and the .410 uses only about a half as much shot as a typical 12-ga. load. Hand loading 12-ga. shells, I must add, can easily save half the cost of factory loads. Problems peculiar to reloading .410 shells include the

narrow selection of suitable components and the inherent sensitivity of

the long column to small changes in the volume of the powder and shot. The

most suitable powders are Du Pont IMR 4227, Hercules 2400,

Winchester-Western 296. The powders are much slower burning than those

used in the larger bores. The slower rate is necessitated by the great

weight of shot load relative to the bore area and because .410 shotcup

wads have no cushion section to allow initial expansion of the gasses as

the shot load begins its travel. Remington 97-4 and Federal 410 primers

are made especially for .410 shells.

|

|

Allowable chamber pressures are slightly higher than for the larger bores, but the resulting force of the gun’s breech is much less because the pressure is applied over a smaller area. A 12-ga. barrel has more than three times the bore area of a .410.

Shotgunners of limited experience are usually more sharply divided in their opinions about the .410 than are experience shooters. Those expressing distain are quick to point out the .410’s ballistic absurdity, particularly with the 3” shell. Tales of un-recovered game and discouraged youngsters are related in endless profusion. On the other hand, those who favor the .410 value its low recoil as well as the diminutive and elegant lines of the guns made possible by the small case. That the .410 bore can and has been used effectively for field wingshooting is beyond question. And it provides the ultimate challenge in American skeet under the present rules.

For the average shooter, .410 guns are seen at their best on the skeet field. Since the days of potshooting birds on the ground are, or at least should be, over, giving a beginner a gun that encourages groundswatting is a travesty. My pattern shooting acquaintance who uses nothing smaller than 28-ga. in the field sets an example which could be usefully emulated by most of us. This man shoots thousands of .410 shells at skeet each year. He says the cripples never get away.

Reprinted curtesy of :- The

Author :- Robert N. Sears

Previously published in "The American Rifleman" May 1981

| <-- Previous Page |

Should a .410 be in your battery? - Page 3 |

|